In the span of about 40 years, the Digital Era has brought new technologies that have benefited people's lives on all continents. However, since the end of the Second World War, the decades from 1980 have seen more economic inequality and concentration of wealth in advanced countries in particular.

Big digital companies are near-monopolies in their markets and can buy young companies to either use new technologies or kill them.

In recent decades aggregate productivity growth has fallen in many economies resulting in poor economic growth trends.

So-called frontier firms are doing well but there are many more laggards.

In May 2022 the Brookings Institution of the United States published a report titled 'An Inclusive Future? Technology, New Dynamics, and Policy Challenges.' It has contributions from leading economists.

The report says "Income inequality has risen in most countries since the 1980s. Practically all major advanced economies have experienced a rise in income inequality, and the increase has been particularly large in the United States, the country at the leading edge of the digital revolution.

Those with middle-class incomes have been squeezed. The typical worker has seen largely stagnant real wages over long periods — and increased anxiety about job loss from automation. Intergenerational economic mobility has declined. Income distribution trends are more mixed in emerging economies but many of them—and most of the major emerging economies — also have experienced rising inequality. Figure 1 shows the trend in the Gini coefficient, a broad measure of inequality, in the 19 major advanced and emerging economies that are members of the G20 (the EU is the 20th)."

Economist Kaushik Basu notes that "paradoxically, productivity growth has slowed rather than accelerated in many economies as digital technologies have boomed. The productivity slowdown extends across OECD economies—and many emerging economies as well. Economic growth, consequently, has trended lower. The twin trends of rising inequality and slower productivity growth are vividly illustrated by the US economy (Figure 3). Since the early 1980s, the share of the top 10% in income in the United States has risen from 34% to 46% (the income share of the top 1% has roughly doubled from 10% to 19%). As for productivity growth, it slowed considerably after the early 2000s. Over the last decade-plus, it has averaged less than half the growth rate of the decade prior to the slowdown."

The proverbial rising tide is not raising all the boats.

Prof Daron Acemoğlu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), has criticised what he terms “excessive automation."

"The reason why, in the ’50s and the ’60s and early ’70s, we had this shared prosperity is because we did have quite a bit of automation. It’s not that there wasn’t automation, but automation was counterbalanced by other technological changes, especially ...new tasks ...And then you look at the 1980s, a completely different picture. What you see is the automation picks up speed, but even more remarkable is all those countervailing types of technologies are absent ...Essentially what we are seeing in the US, and some other economies as well, it’s not only that automation is not being counterbalanced, but it’s actually not sufficiently productive. And it’s not generating the additional labour demand that would come from the productivity effect. And it’s not a surprise to people who have looked at national income accounts, because the last two and a half decades, almost three decades, have seen some of the slowest productivity growth in US history."

Acemoğlu acknowledges that there may be other factors besides technology, such as globalization, that are involved but he says his own research shows that technology is at the forefront.

McKinsey: Forward Thinking on technology and political economy with Daron Acemoğlu (2021)

IMF's Finance & Development publication — Daron Acemoğlu and others (2022)

World Bank: Remaking the Post-Covid World Daron Acemoğlu (2020)

New York Times: Economists pin more blame on tech for rising 1nequality (2022)

"Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything," Paul Krugman, wrote in 'The Age of Diminishing Expectations' (1994). The former Princeton professor, winner of the Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden's Central Bank) Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (informally the Nobel Prize in Economics) in 2008, and economics columnist of The New York Times added "A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker."

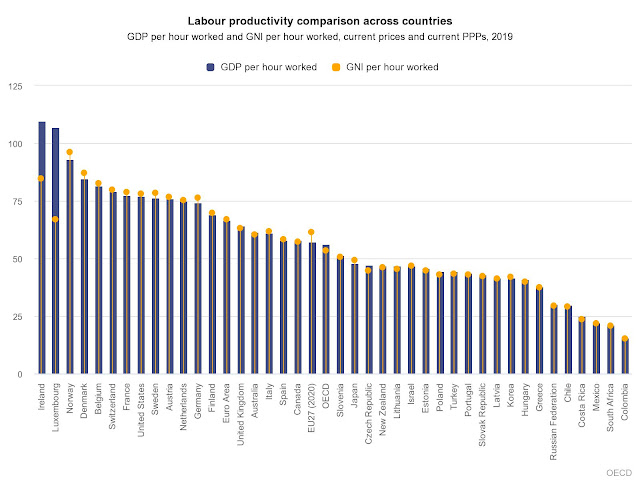

Irish workers seem to be the most productive in the world according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This reflects multinational tax avoidance while Luxembourg's high level mainly reflects the fact that over 40% of its workforce resides outside its borders.

The OECD said in 2021 in respect of 2019 that the Irish added an average of $109.6 (€92.4) to the value of the economy every hour they work compared with an average of almost $60 for the 38 mainly advanced countries of the OECD Area.

GDP (gross domestic product) per hour worked in 2019 was about $75 or more in Norway; Denmark; Belgium; Switzerland; France; the United States; Sweden; Austria; Netherlands; and Germany.

Productivity in Irish indigenous firms remained below the European Union average.

In advanced countries, productivity has been on the slide for a quarter of a century despite the digital revolution.

The Global Financial Recession of 2007-2008 hit productivity hard as countries were experiencing population declines.

Britain

The UK’s output per hour growth between 1997 and 2007 was the second-fastest of the G7 industrialised countries (US, Germany, Japan, France, UK, Italy, Canada). British output per hour grew at an annual average rate of 1.9% but between 2009 and 2019, it was the second slowest, according to the Office of National Statistics. Compared with other G7 countries, the contribution of capital deepening to labour productivity growth in the UK has been weak. This refers to an increase in the proportion of the capital stock to the number of labour hours worked.

In 2019, ranked on GDP per hour worked, the UK came fourth highest among the G7 countries, with France and the US top and Japan at the bottom. UK productivity was around 15% below the US and France.

UK productivity growth averaged 3.0% per annum in the 50 years to 1995.

Total factor productivity (TFP - also called multi-factor) refers to the productivity of all inputs taken together and it is a measure of growth through technological innovation and efficiency achieved by enhanced labour skills and capital management.

A recent issue of The Economist noted:

There is no doubt that the cost of this lost decade was huge. Had Britain’s productivity growth rate not fallen after the global financial crisis, GDP per person in 2019 would have been £6,700 ($8,380) higher than it turned out to be. But there is fierce debate over what exactly went wrong. Diane Coyle, a director of the Productivity Institute, a research consortium, likens the search for a source of Britain’s weak productivity growth to the conclusion of an Agatha Christie mystery. “Everybody turns out to have done it.”

Several enormous shocks hit the British economy over the course of that decade, even before the pandemic delivered another. The financial crisis curbed the flow of credit. One study published in 2020 found that companies with weaker pre-crisis balance-sheets that faced a particularly severe reduction in credit saw sharper reductions in TFP growth, partly because they cut back on innovation. Drooping demand crimped incentives to invest and innovate: around half of European economists surveyed in February 2020 attributed Britain’s slowdown to weak demand associated with the financial crisis or austerity policies.

Then there is the Brexit albatross and the reliance on London for generating almost a quarter of GDP.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland has a 15% gap to the UK level when measured by GVA (gross value added) per job, widening to 18% when measured per hour worked.

A report on productivity noted "Research has identified a number of potential explanations for Northern Ireland’s persistent productivity gap. The local economy has a relatively higher concentration of low-productivity sectors. It is geographically peripheral, while an infrastructure gap within Northern Ireland may also exist. Levels of investment in research and development in Northern Ireland are below the UK average, while levels of human capital are particularly low. Finally, both public policy, and institutions and governance, may contribute to the productivity gap."

It added "Northern Ireland possesses a skills gap to the rest of the UK. The policy, therefore, needs to identify how to improve skills, alongside ways to attract firms and industries which can take advantage of a more highly skilled workforce. Secondly, Northern Ireland not only has a relatively higher concentration of low productivity sectors, it also has a long tail of low productivity firms within sectors."

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, the Central Statistics Office (CSO) published productivity data for 2019 in 2021. The foreign-owned sector had an annual average 2000-2019 Labour Productivity of 8.8%; the EU was at 1% and the Irish-owned sector was at 0.8%.

However, the Irish National Competitiveness and Productivity Council warned "it should be noted that the productivity performance of the Domestic and Other sector is ...likely to be influenced by a number of traditionally domestic industries (e.g. Food & Beverages) which over time have shown an increasing share of foreign value-added or turnover, according to the CSO Structural Business Statistics. Since these foreign-owned enterprises have relatively higher productivity than the Irish-owned enterprises in this broad sector, the productivity growth of Irish-owned enterprises in the ‘Domestic and other’ sector could be even lower."

Foreign-owned firms dominate Irish tradeable manufacturing and services and, a paper published by the ESRI (Economic and Social Research Institute) in 2018 noted that "Overall, we find fairly limited evidence of a link between the presence of foreign-owned firms and the performance of domestic firms..."

Ireland has one of the lowest levels of employer dynamism (births and deaths of enterprises) in the OECD Area.

Exports by small and medium (SME) size Irish employer firms are in the single digits along with Greece.

A paradox

In 1987 American economist Robert M. Solow was awarded the Sveriges Riksbank's Economic Sciences Prize. In July of that year, he wrote a book review for the New York Times Book Review titled 'We'd Better Watch Out.'

The authors were concerned that American manufacturing had become uncompetitive.

Solow wrote "The trouble is that they do not know, any more than I do, exactly what let Japan and West Germany overtake United States industry ...What this means is that they, like everyone else, are somewhat embarrassed by the fact that what everyone feels to have been a technological revolution, a drastic change in our productive lives, has been accompanied everywhere, including Japan, by a slowing- down of productivity growth, not by a step up. You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics."

This became known as the Solow Paradox.

In 1969, a computer at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) and one at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), were connected in the first network to use packet switching: the US Defense Department's Advanced Research Projects Agency Network, or ARPANET.

In 1989 Sir Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in Switzerland.

The United States produced about 40% of the global semiconductors in the 1990s and the cost of chips fell.

US labour productivity grew at an average rate of 3.3% in 1998-2005. The Bureau of Statistics estimates that the "figure — $10.9trn — represents the cumulative loss in output in the US nonfarm business sector due to the labour productivity slowdown since 2005, also corresponding to a loss of $95,000 in output per worker. It has been suggested that past measures may have exaggerated the outcomes.

Some technologies take decades to become widely adopted.

Illustrating the potential of AI (Artificial Intelligence) as a general-purpose technology, the MIT Technology Review says Scott Stern of MIT’s Sloan School of Management describes it as a “method for a new method of invention.” An AI algorithm can comb through vast amounts of data, finding hidden patterns and predicting possibilities for, say, a better drug or a material for more efficient solar cells. It has, he says, “the potential to transform how we do innovation.”

However, he also warns against expecting such a change to show up in macroeconomic measurements anytime soon. “If I tell you we’re having an innovation explosion, check back with me in 2050 and I’ll show you the impacts,” he says. General-purpose technologies, he adds, “take a lifetime to reorganize around.”

Economists at the Organisation of Cooperation and Economic Development (OECD) used a sample of 24 countries where the top 5% of performers were called frontier firms where labour productivity at the global frontier increased at an average annual rate of 2.8% in the manufacturing sector, compared to productivity gains of just 0.6% for laggards. The findings were published in 2015.

Frontier firms reap high profits and they typically dominate their industry.

Between 2001 and 2013, in OECD economies, labour productivity among frontier firms rose by around 35%; among non-frontier firms, the increase was only around 5%.

A European Central Bank (ECB) 2021 paper notes that technology is a key factor driving within-firm productivity growth. However, this factor plays a less prominent role in productivity growth in EU countries than in the United States and may be slowing down in EU countries.

"Three findings support this statement.

(a) Productivity growth in the information and communication technology (ICT) sectors of EU countries is much lower than in the United States. More broadly, technology-intensive sectors drive aggregate productivity growth to a larger extent in the United States than in Europe.

(b) There is some evidence, both macro-based and micro-based, that innovation in the manufacturing sector has been slowing in both the United States and the EU. The macro evidence shows that patenting activity has been flat since the global financial crisis in both regions. In addition, the United States and the EU’s market share of high-technology manufacturing exports has declined sharply over time, to the benefit of China. This finding is supported by evidence-based on firm-level data, showing a slowdown in technology creation by EU manufacturing firms at the frontier. This slowdown is concentrated in high-technology sectors.

(c) Technology creation in services has accelerated over time in the EU. However, the productivity gains from this development seem to be benefiting relatively few services firms at the frontier. Laggards in services continue to show low levels of productivity growth. This evidence points to a slowdown in technology diffusion in the services sector."

Two-thirds of developing countries dependent on commodities

8.4% of world population live in a full democracy including Ireland

44% of US workers in low-paid jobs with a median hourly pay of $10