On December 6, 2019, King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands (left) opened Unilever’s new global Foods Innovation Centre on the campus of Wageningen University, the leading global agri-food research hub. Unilever invested €85m in the new centre, named ‘Hive’ for its location amidst leading academic research centres, startups and external partners. From Hive, Unilever said it would lead its global foods innovation programs for brands like Knorr, Hellmann’s, The Vegetarian Butcher and Calvė. Areas of research include: plant-based ingredients and meat alternatives, efficient crops, sustainable food packaging and nutritious foods. The consumer goods giant said the energy-neutral Foods Innovation Centre, was rated “Outstanding” by the Dutch BREEAM assessment body for environmental performance, putting it among the most sustainable multifunctional buildings in the world.

Rising global population coupled with climate change, present enormous challenges. According to a 2019 United Nations report, since the pre-industrial period (1850-1900), the land surface air temperature has risen nearly twice as much as the global average temperature.

In primary production (crops and animals from agriculture and fishing) each degree-Celsius rise in global mean temperature would, on average, reduce global yields of wheat by 6.0%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4%, and soybean by 3.1%. It would, of course, vary between regions and scientists are seeking to for example "train crops like maize and wheat to produce their own nitrogen fertiliser from the air — which soybeans and other legumes (e.g. beans, peas, lentils, and peanuts) use — and they are also exploring how to make wheat and rice better at photosynthesis in very hot conditions." See here.

At the country level, food innovation involves both primary production and secondary processing that produces products for consumers. Environment, health, sustainability, nutrition, and waste mitigation are key factors — the UN report cited above noted, "Currently, 25–30% of total food produced is lost or wasted."

The Netherlands and Denmark are food innovation powerhouses and this year Switzerland, another small country with an economy that is a global innovation leader, announced a plan to develop a food innovation cluster/ hub in the Alpine country, led by Nestlé — the biggest food company in the world — and the research institute EPFL (Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne).

Michael Porter of Harvard Business School in a 1998 article in the Harvard Business Review defined business clusters as "geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field." He wrote:

"Clusters are a striking feature of virtually every national, regional, state, and even metropolitan economy, especially in more economically advanced nations. Silicon Valley and Hollywood may be the world’s best-known clusters. Clusters are not unique, however; they are highly typical — and therein lies a paradox: the enduring competitive advantages in a global economy lie increasingly in local things — knowledge, relationships, motivation — that distant rivals cannot match."

This year AgFunder, a venture capital tracker, reported that "AgAgri-FoodTech investment continues to break records, reaching a staggering $20bn in 2019, up more than 6x from 2012."

The focus in this analysis here is on small European economies that are global innovation leaders and how Ireland, in particular, can reduce beef production as agriculture in Ireland accounts for a third of greenhouse gas emissions, while embracing agri-tech.

In 2019 Switzerland was ranked No. 1 of 129 countries in the Global Innovation Index, which is produced by Cornell University, INSEAD Business School, and the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). The Netherlands got a 4th rank and Denmark a 7th. The 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index ranked Germany No. 1, Switzerland 4th, Denmark 8th and the Netherlands 13th. The 2019 European Union' innovation scorecard has Sweden with a top-ranking and Denmark and the Netherlands at 3rd and 4th.

Data for Ireland in respect of GDP; high tech output, exports and personnel; licensing fees; Intellectual Property (IP) and inward and outward FDI, are not reliable.

The Netherlands

"God made the earth, but the Dutch made Holland" is a common expression in the Netherlands (Holland refers to the 2 of 12 provinces — Noord-Holland and Zuid-Holland. However Holland is often used as a substitute for the kingdom of the Netherlands.)

The centuries-old battle of taming the North Sea and developing canals promoted technology and urbanisation while the Dutch Republic (1581-1795) also known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, became Europe's richest country.

The Dutch Republic became the First Modern Economy in the world from the early years of the 17th century.

The Netherlands today is the second biggest exporter of food worldwide, topped only by the US (which has 270 times its landmass). More than half the country’s land is used for agriculture and horticulture. There are more than 6,000 agriculture/food companies based in the country, as well as units of some of the world’s largest producers and R&D facilities.

The Netherlands has a population of 17.2m and it is the No. 1 exporter of potatoes, onions, and fresh vegetables. In tomatoes in 2019, it was second with a share of 22%, behind Mexico at 24.1%.

In 2017 foreign-owned multinationals were responsible for 53% of goods export value and 62% of service exports value.

Potatoes are Ireland's biggest vegetable import and the net imports of fruit and vegetables are valued at about €1bn annually.

Beyond its agricultural expertise, the Netherlands could not have achieved its prominence in the agri-food industry without the extensive research and knowledge cultivated in its R&D clusters/ hubs.

The Food Valley cluster/ hub in Wageningen, a town with a population of about 40,000 in the province of Gelderland, East Netherlands, has developed from 2004. At the hub's core is Wageningen University & Research (WUR), which was founded as a university in 1918 having previously been an agricultural college.

WUR, the University of California Davis, and Cornell University in the US are the world’s leading research centres for food technology.

The hub has about 200 companies to the 10km radius around Wageningen, with startups to big firms such as Royal FrieslandCampina, the Dutch dairy cooperative, Kraft Heinz and of course Unilever.

Keygene a Dutch firm that specialises in crop improvement by molecular breeding says, "This non-GM approach is the fastest and most cost-effective technique to support breeding and food companies bring better crops to market."

Mosa Meat is a cultured meat startup based in Maastricht. The company says its team, including Prof Mark Post, chief scientific officer, and Peter Verstrate, chief operational officer, created the world's first cultured hamburger — that is, real meat grown directly from animal cells rather than raising and slaughtering an animal. "Having proven the concept, we launched Mosa Meat (a spin-out from Maastricht University) to develop commercial products and introduce them to the market. Our mission and driving motivation are to revolutionise the way we produce meat so that we can satisfy soaring demand with meat products that are healthier, better for the environment and kinder to animals."

Along with the 6,000 agri-food companies, one out of every six industry employees work in the food industry. According to the Food Valley organisation, the food industry has 140.000 people employed while the agricultural industry consists of 54,000 companies with 176,000 employed.

Invest in Holland says:

[Nearly two decades ago, the Dutch made a commitment to sustainable agriculture by following the approach “produce twice as much food using half of the resources.” This led to the reduction of water dependence for key crops by as much as 90%. Dutch farmers have almost completely eliminated the use of chemical pesticides on plants in greenhouses, and since 2009 Dutch poultry and livestock producers have cut their use of antibiotics by as much as 60%.]

2019 performance

In 2019, the Netherlands exported €94.5bn worth of agricultural goods. The export of agriculture-related technology goods grew by 8% to a value of €9.9bn. These figures are from Wageningen Economic Research and Statistics Netherlands (CBS) on behalf of the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality.

As in previous years, most of the agricultural exports in 2019 went to neighbouring countries. A quarter of the total estimated exports went to Germany (€23.6bn), followed by Belgium (€10.8bn), the UK (€8.7bn) and France (€7.7bn) — the four countries account for 54% of all Dutch agricultural exports.

Primary (i.e. unprocessed) and secondary (i.e. processed) agricultural goods contributed almost a net €42bn to the Dutch economy last year (exports minus the import value of goods and services). The vast majority (92%) of exports were products made in the Netherlands, while the remaining 8% came from goods that were first imported before undergoing limited processing and then exported. The most profitable export sectors for the Netherlands are ornamental plants and flowers (€5.8bn), dairy products and eggs (€4.3bn), meat (€4.0bn) and vegetables (€3.5 bn).

National Geographic Sept 2017: This Tiny Country Feeds the World

Denmark

Denmark has a population of 5.8m and 25% of Denmark’s total merchandise exports are related to the food industry.

Denmark like Ireland was dependent on agricultural exports in the 1950s. Today it is home to wind turbine giant Vestas and the world’s biggest developer of offshore wind. It began focussing on wind power in the 1970s. In 2019 almost half its electricity consumption came from wind power.

Danish-owned firms are responsible for about two-thirds of the value of its goods and services exports.

Danish companies have an estimated 14% share of the global ingredients market — exporting as much as 98% of the ingredients they produce.

There is a history of ingredient innovation ever since the 19th century when the first pioneering work took place in the Carlsberg Laboratory, the Chr. Hansen Labs and the chemical laboratory at the University of Copenhagen.

Today, Denmark is a leader in areas such as enzymes, emulsifiers, cultures, natural food dyes, flavours and whey protein. A lot of that innovation is the fruit of close research cooperation between businesses and universities.

The Danish Food Cluster dates from 2013 and it has about 150 member companies that account for 75% of the Danish food industry. It is located in the region of Aarhus, a city on the East Jutland coast. Aarhus University in addition to its main campus in Aarhus, also has campuses in Herning and Emdrup, as well as research activities in 18 different locations in Denmark, Greenland and Tenerife.

Danish Crown — Europe's biggest meat processor (pigs) — and Arla — the Danish-Swedish multinational dairy group — have facilities there as well as Nestlé and DMK — Germany's biggest dairy company.

At the other end of the spectrum, Argointelli with about 30 permanent employees in the cluster, says it's a "development house" for machinery manufacturers, who want to be among the leading technological innovators.

Denmark announced in January the merger of 5 medical clusters. It is home to around 1,000 companies that operate in the medtech field. More than 250 are dedicated medtech companies.

Agri tech and food tech

Both the Netherlands and Denmark export food-related technologies.

Wageningen researchers are developing robots that can do agricultural work, such as weeding, harvesting, and packing, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Utilising cameras and sensors, these motorised robot platforms and hands are more precise than human beings. For example, collecting eggs, packing tomatoes, weeding, checking animal welfare, harvesting fruits, and detecting pests in crops. These are all things that will be performed by robots in the not-too-distant future.

Erik Pekkeriet, business development manager for the Agro Food Robotics programme (not to be confused with the English word aggro!) has said that primarily due to increased mechanisation and ICT, working conditions have declined. The work used to be varied and people were able to stop and chat with each other. Now they work by themselves or together in noisy rooms with earplugs and protective clothing. “Social interaction is barely possible and people do the same thing all day long. The human component of the work is very monotonous and extremely repetitive,” added Pekkeriet. The number of Polish workers in Dutch agriculture has declined.

According to ING, the Dutch bank, robots are increasingly used within food production since innovations in image recognition technology and gripper technology have enabled robots to see and feel. This allows them to handle delicate and diverse food products and function in challenging environments, including heat, moisture and cold. At the same time, less human interference also reduces the risk of contamination, helping producers comply with strict food safety requirements.

In Europe, robot sales to the food industry increased with 50% over the last five years.

European food manufacturers account for almost half of the current worldwide robot stock in the food industry. The level of robotisation in the industry varies significantly between countries. Robot density, the number of robots per 10,000 employees, is especially high in Sweden and Denmark. These countries have relatively high labour costs, just like runner-ups including the Netherlands and Italy, increasing the need to automate manual labour.

Ireland

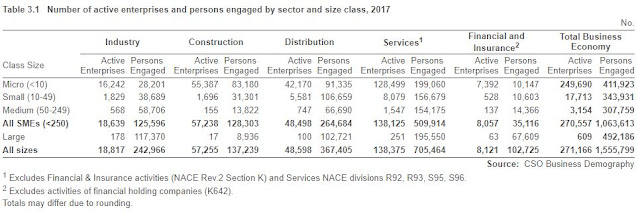

In 2019 the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published a report on Irish micro (1-9 employees), small (10-49) and medium-sized companies (50-249) [SMEs] titled 'SME and Entrepreneurship Policy in Ireland.'

At a conference in Dublin in July 2019 where the report was launched, Leo Varadkar, taoiseach, and Heather Humphrey, minister for business, announced a new policy for the growth of the SME sector as part of its Future Jobs strategy.

Ulrik Vestergaard, OECD deputy general secretary, told the Future Jobs Ireland conference in the Aviva stadium that only 6.3% of Irish SMEs export, which put Ireland and Greece in the lowest ranks in the EU.

The 6.3% number was my estimate in 2016 based on 95,000 employer firms, with from 1 employee. At the time the Central Statistics Office (CSO) did not separately publish the number of employer firms in its total estimate of active enterprises.

The chart above uses Eurostat data for 2017 which shows that Ireland had over 114,000 employer firms. The total for exporters relates to merchandise trade.

The latest Irish export firm ratio is 7.5%.

Kris Boschmans who works as a policy analyst for the Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities at the OECD, told the conference that productivity in the SME sector has been in decline in recent years. He said that it was “a bit surprising to see that so few Irish SMEs are internationally active” and that startup rates in Ireland were also below the OECD average.

In 2016 the CSO estimated that half of 6,800 Irish exporters to the UK only export to that market.

The OECD report notes on clusters, "While Ireland thus has taken initiatives to foster enterprise-led networks, it has not yet implemented a coherent national cluster policy, which could be a means to engage SMEs more intensively in economic development projects. There is scope to learn from other countries that have introduced more forceful national policies in this respect."

Claudia Dorr-Voss, German state secretary for economic affairs, told the Future Jobs Ireland conference that Germany had 87 clusters with 15,000 institutions and 10,000 SME companies involved.

Enterprise Ireland, the national enterprise agency supporting indigenous industry, has a positive but delusional story:

"Ireland is a world leader in key innovative sectors...Ireland - home to world class research and development facilities and expertise...Ireland - Home to High Potential Start-Up Companies."

However, the first step in a 10 to 20-year plan to move indigenous Irish enterprises from stagnation, is to acknowledge the deficiencies raised by the OECD and by myself over many years.

Developing new overseas markets is a hard slog and I have often cited the very low value of indigenous exports of €5bn to the 340m population Euro Area in 2018, despite 20 years of no foreign exchange volatility.

The lazy Irish assumption that there is no need to have competence in a local language in Europe to develop good relations with counterparts, is foolish.

Trinity College, the University of Dublin, is promoting the development of an innovation district — an alternative name for a technology cluster — in the Irish capital. It hopes to raise €1bn to fund the project.

Patrick Prendergast, the provost of the university, said in 2016 “So much of the tech industry is going on here. Google, Facebook, Twitter, Airbnb — and it’s all right beside where we have our technology and enterprise centre.”

However, what is "going on" is not high-level innovation but mainly administration and sales support functions handled by personnel from various European countries, with competence in languages other than English.

In the 1990s there were high hopes for the indigenous high tech and biotech sectors but in contrast with Denmark with its long tradition in pharmaceuticals, the optimism faded. There have been some Irish stars that were snapped up by overseas firms but there has been no scaleup in Ireland.

Twenty years ago Elan, founded by an American in Athlone in 1969, was the 20th most valuable drugs company in the world and 13 years later it was asset-stripped and the rump was sold to an American white goods drug firm. The once tech star IONA Technologies was a spinout from Trinity College in 1991. Its value peaked at $2.22bn during the dot-com bubble and in 2008 it was sold to an American firm for $162m and its name disappeared.

Policy makers tend to be dazzled by high tech and its potential as a jobs maker.

However, Irish policy makers should turn their attention to the potential of food innovation. It's the sector with the strongest economic linkages.

According to a survey by the Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation Irish owned companies in 2017 spent €25.1bn of direct expenditure (payroll, materials and services) in the Irish economy compared with €21.3bn for foreign owned exporting companies. The charts above show that Irish-owned companies in Food & Drink spent 77.6%/ 84% in Ireland while foreign companies in Chemicals (pharmaceuticals) spent 6.6%/ 5.4%. Payroll costs for foreign firms were higher than the indigenous ones.

An Irish Food Cluster should be created.

In 2015 the Kerry Group's innovation centre in Naas, County Kildare was opened. There was an investment of €100m and it hosts about 800 jobs and 32 nationalities.

Kerry had a 436th ranking in the top 2,500 global companies ranked by R&D and issued last December by the European Commission. Kerry's research and development (R&D) spending was €236m in 2018. Glanbia was at rank 2,249 with a spend of €36m. There was no other Irish food and beverage entrant.

Nestlé had a rank of 82, spending €1.763bn.

This year there was no Irish entrant in the Financial Times' top 1000 fastest growing companies.

Norway was the second biggest fish exporter, after China in 2018. It sold about $12bn worth of fish and aquaculture represented about 71% by value and 45% by volume of the exports.

Irish seafood exports were worth €605m in 2019 while imports were at about €300m. Overall food exports were valued at €11.7bn; import value was €7.9bn. Beverage exports were at €1.4bn and imports were valued at €910m.

The Netherlands' agri-food exports value was over seven times the Irish level in 2019.

We can do better than our current poor record.

Finally, there is a successful Irish food industry example that dates from 1965 when 4 West Cork dairy co-operatives — Bandon, Barryroe, Drinagh and Lisavaird — teamed up with Express Dairies of the UK to open a cheese factory near the village of Ballineen, west of my hometown of Bandon.

Last December Carbery Milk Products, which is now 100% owned by the 4 dairy co-ops got a €35m loan from the European Investment Bank (EIB) to fund a €78m investment to drive global expansion. A new mozzarella production facility will support 1,200 Irish farmers.

Carbery is a multinational operation producing food ingredients, flavours and cheese. In 2019 it had revenues of €434m and it has a staff total of about 700 people.

State of Irish high tech and biotech 2020